Robert FELLOWS and Rose HENRICKSEN

Relationship to me: Great Grandparents (paternal)

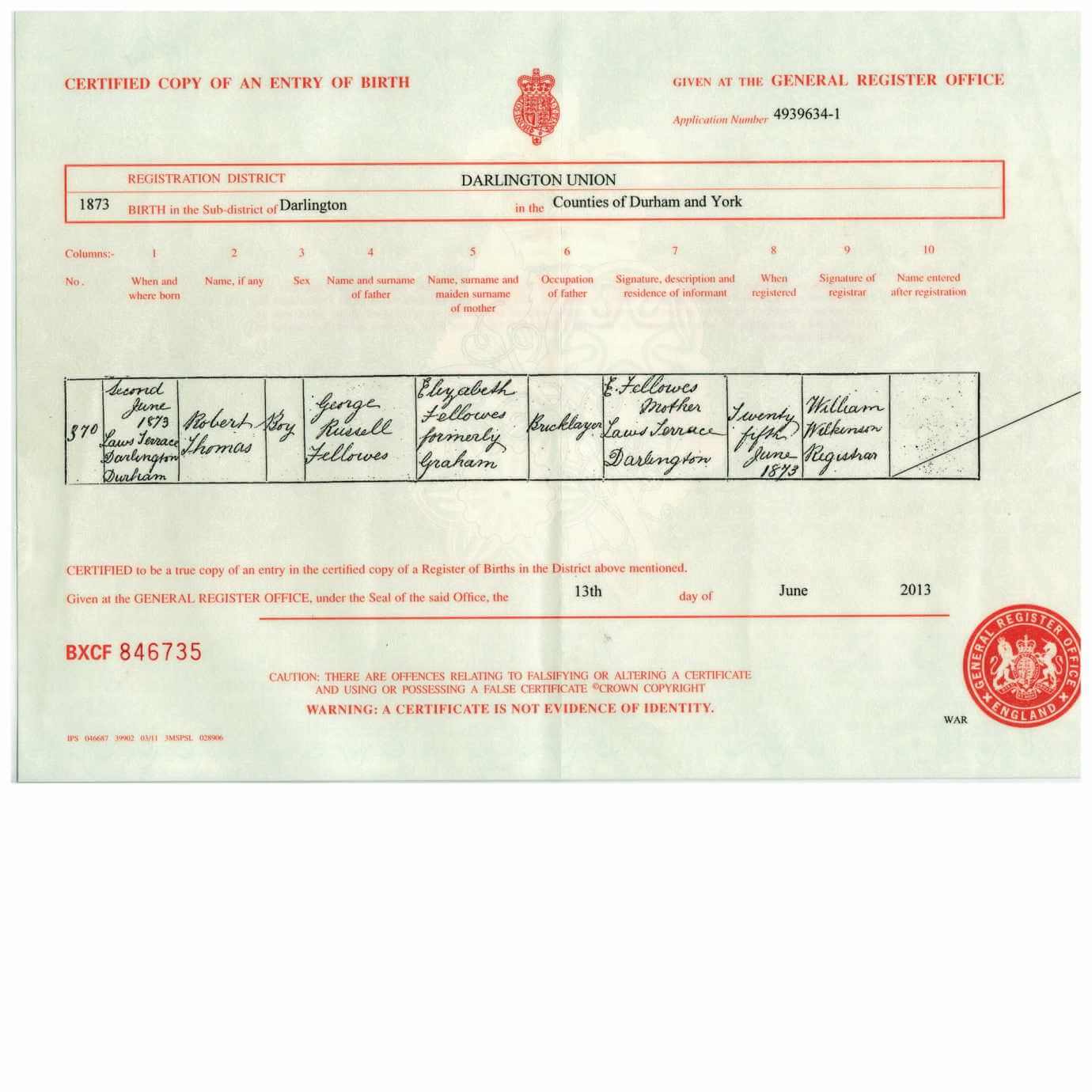

Robert was born in England on June 2nd, 1873 and travelled to New Zealand on the “May Queen” with his parents and two brothers in 1881 when he was eight years old. The family left England on 26 August 1881 and arrived on 16 Dec 1881. Rose was born in Dunedin in New Zealand but we know nothing about her parents or where they were from. More on this below!

Robert and Rose were married on June 22, 1893. Robert was a lighthouse keeper in the early years of their marriage and they lived in at least four different lighthouses around the New Zealand coastline.

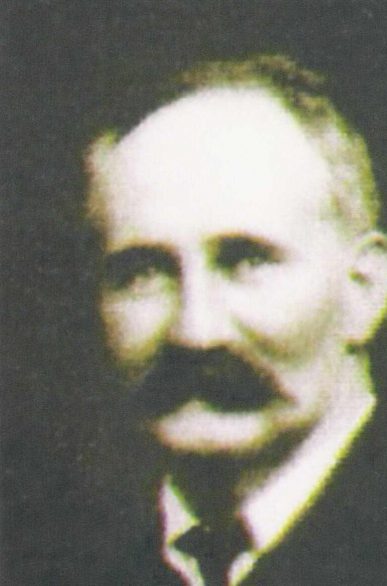

Robert Thomas FELLOWS

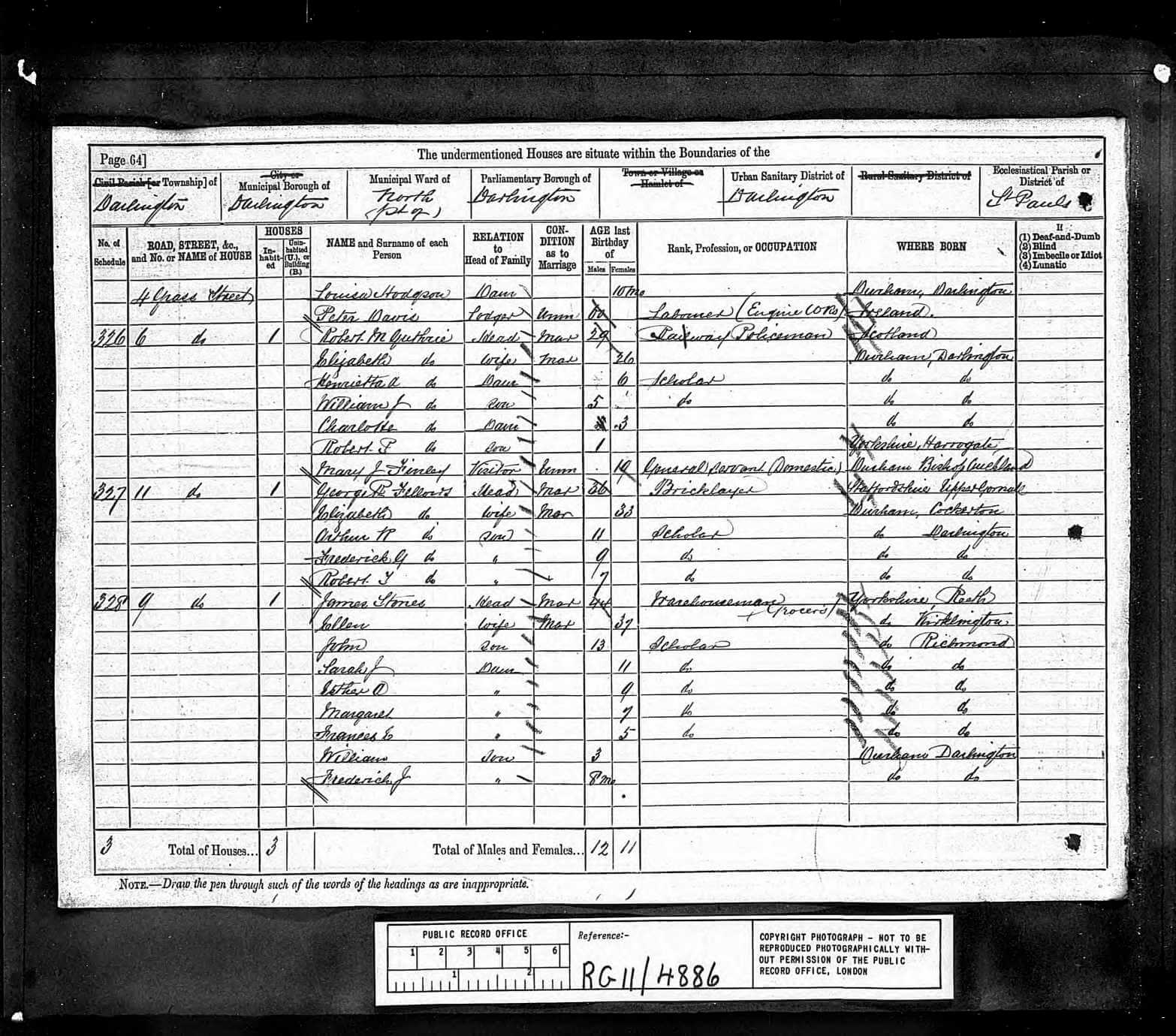

Robert was born on June 2nd, 1873, in Laws Terrace, Darlington, Durham, England. He was the youngest of three boys born to George Russell FELLOWS and Elizabeth GRAHAM. On August 22nd, 1881, George and Elizabeth arrived in New Zealand with their children about the “May Queen.”

Robert and Rose married on June 22nd 1893 at the registrars office in Auckland. Robert worked as a bricklayer like his father. He died of chronic myocarditis on February 25th, 1940 at his home at 118 Nelson Street in Auckland and is buried at Purewa Cemetery.

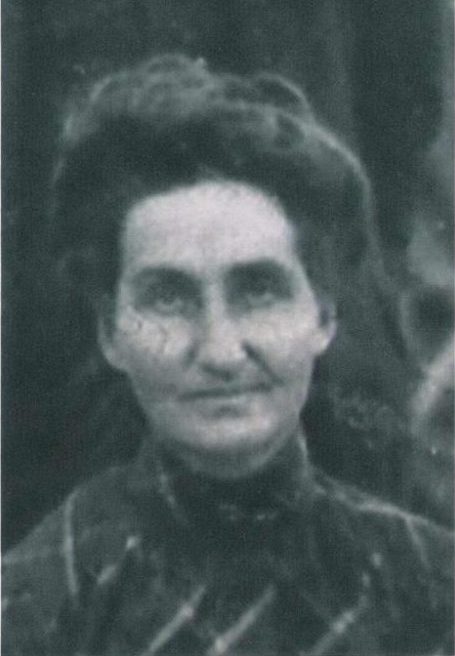

Rose Ann Adelaide HENRICKSEN

I think that Rose’s surname was originally FERGUSON or HARRIS but haven’t been able to find any birth records for her. Her marriage certificate says that she was born in Dunedin, New Zealand with parents unknown.

Rose died on June 11th, 1938, in Auckland Hospital. She died of congestive heart failure after having cerebral thrombosis for several months and is buried in Purewa Cemetery. This is the same cemetery where her daughter Eileen Lilac was buried at just five years of age (died 15 Dec 1915, buried 22 Dec 1915).

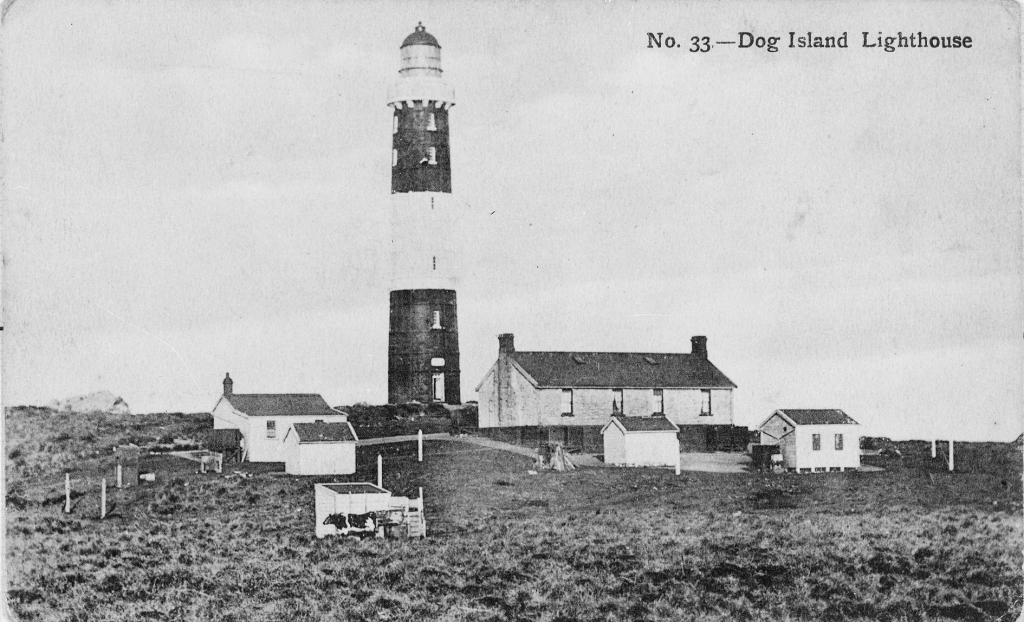

Lighthouse Keeper

For several years of their early married life, Robert was a lighthouse keeper. He first worked at the Dog Island lighthouse from 1900-1903 as the assistant keeper, then the Moeraki Lighthouse in Otago from 1905-1906. They would have lived at the lighthouse with four young children. Between 1907-1910, Robert was listed as the assistant keeper at Waipapa. In 1911, Robert and Rose are listed as living in Huia, again with Robert working as a lighthouse keeper. In 1911-1912 Robert was working at East Cape Lighthouse. He resigned from service in 1914. This was confirmed through electoral rolls and newspaper reports.

Dog Island lighthouse is one of the oldest and tallest (36 metres) lighthouses in New Zealand, located off the southern coast of the South Island. The tower is painted with two black stripes to make it more easily seen, one of only three lighthouses in NZ painted with stripes. The tower was built from stone quarried from Dog Island and started operating in 1865. Maritime NZ notes that in its early years, and likely up until the time that Robert and his family lived there, the mechanism had to be wound up by the keepers. In 1883, the principal keeper died when he fell down a 23 metre shaft that ran down the centre of the lighthouse while adding a weight to increase the revolving light speed. Dog Island, or Moto-piu in Te Reo which means “swinging island”, was a difficult place for keepers and their families since it was not possible for children to travel to the mainland for school. Supplies were sent every three months by ship. It’s hard to imagine Robert and Rose living here with their four young children given how desolate and isolated it is.

Moeraki is located just north of Dunedin. The lighthouse was operational from 1878 and had resident keepers until 1975 when it was automated. The station had two keepers each with their own two-bedroom house. Moeraki had a small settlement and a school so it was desirable for keepers who had families.

The Waipapa lighthouse is one of only two remaining wooden lighthouses in New Zealand. It is on the southernmost tip of the South Island and was built in response to the wreck of the Tararua passenger steamer.

Sailing from Port Chalmers, Dunedin at 5 pm on 28 April 1881, the Tararua was en route to Melbourne via Bluff and Hobart. Steering by land on a dark night, with clear skies overhead but a haze over the land, the captain turned the ship west at 4 am believing they had cleared the southernmost point. After breakers were heard at 4:25 am, they steered away to the W by S-half-S for 20 minutes before heading west again. At around 5 am, the ship struck the Otara Reef, which runs 13 km (8 mi) out from Waipapa Point.

The first lifeboat was holed as it was launched, but the second lifeboat carried a volunteer close enough in to swim to shore and raise the alarm. A farmhand rode 35 miles (56 km) to Wyndham to telegraph the news. However, while a message reached Dunedin by 1 pm, it was not marked urgent, and it took until 5 pm for the Hawea to leave port with supplies. Meanwhile, the wind and waves had risen. Around noon, six passengers who were strong swimmers were taken close to shore; three managed to get through the surf, with the help of the earlier volunteer, but the others drowned. On a return trip, one man attempted to get ashore on the reef, but had to give up; another three drowned trying to swim to the beach. Another boat capsized trying to get a line through the surf. Eight of its nine crew survived, but the boat was damaged, and the locals who had gathered on the shore could not repair it. The remaining boat could no longer reach the ship, due to the waves, and stood out to sea in hope of flagging down a passing ship to help. The Tararua took over 20 hours to sink, with the stern going under around 2 pm and the rest disappearing overnight. The last cries of the victims were heard at 2:35 am. Only one man managed to swim safely from the ship to shore.

About 74 bodies were recovered, of which 55 were buried in a nearby plot that came to be known as the “Tararua Acre”. Three gravestones and a memorial plinth remain there today.

Wikipedia, SS Tararua

A subsequent court of inquiry found that there were only 12 lifebelts on board the ship, resulting in the law changing and requiring a lifebelt for every passenger.

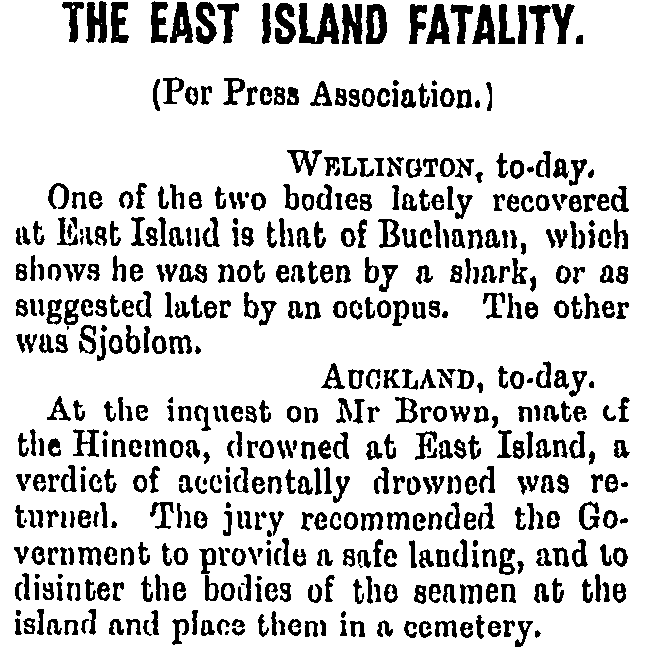

East Cape lighthouse was first built in 1898 on Whangaokena (East Island) and was operational from 1900. This is the most easterly point in New Zealand and the first place in the world to greet the morning sun. The tiny island, just 13 hectares in size, is called Whangaokeno or Motu o Kaiawa in Te Aro Maori. Initially, the lighthouse was lit with a paraffin oil-burning lamp which was later replaced with an incandescent oil-burning lamp. In order to get supplies to the lighthouse, a large concrete block was placed at the western end of the island on the beach with a wire rope running to a winch at the top of the cliff. In the first month after the lighthouse became operational, the winch and wire ropeway was washed away by heavy rains. Mail was irregularly received from a local Maori mailman and the Hinemoa arrived every four months to bring supplies. The Maori believed the island was tapu (spiritually restricted) and as a result, no Maori person ever lived on the island. Lighthouse keepers and their families were unable to ever grow vegetables or keep livestock alive because of the poor soil, and there were frequent landslides and earthquakes, so maybe there was some truth to this!

Three sailors’ lives were lost in 1899 when they left the Hinemoa and attempted to land at Whangaokena. As they approached the shore heavy seas caused their boat to capsize. One of the men’s bodies was returned to Wellington to his family while the other two were buried on Whangaokena. It was not until 1902 that a telephone line was installed to the mainland, giving the keepers and their families connection to loved ones. The same year, the lighthouse was established as a post office – one of only 15 around New Zealand. By 1906, there were seven souls in the graveyard on the island, including the three children of keepers. In July 1906, the ketch Sir Henry was wrecked on the island causing three lives to be lost. The light was extinguished in 1922 and the tower was moved to the mainland. The keeper houses were left abandoned until 1930 when a local farmer, George Goldsmith, moved to the island to dismantle the buildings. With the help of other local men, he lashed the timbers of the buildings together and floated them to the mainland as a raft. It took nine months to move all the buildings but they managed to do so without breaking a single pane of glass. George returned in later years to help eradicate the goats on the island that had been destroying the local fauna.

In 1919, Robert is listed as a builder and later that year as a signalman. In 1928 he is listed as working as an AHB employee although I have been unable to confirm what AHB produced. It was possibly the animal health board. By 1940 he is listed as working as a nightwatchman.

Challenges of Being a Lighthouse Keeper

Angela Bain highlights some of the challenges of being a lighthouse keeper and the rules they had to comply with.

Instructions to Lightkeepers, written in 1866, set out the criteria which prospective keepers had to meet before being employed by the Light Service. The applicant had to forward the application ‘ in his own handwriting’ and include a ‘ certificate of good conduct’ from his last employer, and letters from ‘ each of the gentlemen by whom he is recommended ’. The letters were to show that the applicant had, to the writer’s knowledge, been ‘ sober, honest, industrious and obliging, and has enjoyed good health ’. If he was selected to progress past the application stage, the man had to undergo a medical examination and have his eyesight tested. The 1886 version of Instructions to Lightkeepers set out further specifications. Keepers had to be aged between 21 and 31 when they joined the Service, had to be able to read and write and have ‘ a fair knowledge of arithmetic’, and be ‘ healthy and robust in constitution ’. In later years, preference was given to men with trade experience as all keepers were encouraged to be handy men and ‘ do-it themselves’ whenever possible.

With keepers living so closely together, some conflict was inevitable. Sometimes the problem was simply a clash of personalities, other times it was how well a keeper performed his duties. Assistant Keeper Payn arrived at Puysegur Point in February 1887. In October, Principal Keeper McNeil complained to the Marine Department about his conduct, saying — I got nothing but abuse and this kind of conduct is becoming daily

worse tonight [sic] he refused to keep the first watch. Payn was discharged from the Service in January 1888 as a result of these allegations. Around the same time at Waipapa Point, Principal Keeper Ericson and Assistant Keeper Nicolson were engaging in a war of letters to the Marine Department, each complaining about the other. It began with Ericson complaining about the dirty state of Nicolson’s house and escalated into character attacks by both men. Nicolson said he had been — Subject to verry [sic] foul and insulting language from the Principal Keeper who is an expert at such … I would request that you order him to stop it. Ericson accused Nicolson of using abusive language and of cruelty to the station horse. Their relationship became so bad that an inquiry was carried out into the situation in December 1887, and Nicolson was removed from the station.367

In May 1907, Principal Keeper Scott of Centre Island wrote to the Marine Department saying — With regards to Keeper Pepper I would like very much if you could remove him to another Station as he is a very undesirable person to have on a station where women and girls are, the Brothers would be a more suitable place for him. A month later, Pepper resigned from his Centre Island position. Scott said — …the reason that I asked for a shift for him and was that he was continually scratching his person and he could not see any of the women or girls outside the house but he would be in their company whether they liked it or not and continued the scratching when in their company.

A Change of Name

There are two stories about how Rose’s surname changed but I have been unable to confirm either of them.

The first story is that her father died, when Rose was 3 or 4 years old, in a work accident, and friends of the family, Peter Henricksen and Victoria Grant, travelled down from Auckland to take care of her and returned to Auckland with Rose. This story is based on Rose’s parents being Hannah SOLOMON and George HARRIS, a bootmaker in Dunedin. A descendent told me that Rose’s mother had died, her father was away from Dunedin attending her funeral, and Peter and Victoria Henricksen came to help and took Rose back with them. Unfortunately, Peter’s will does not mention Rose at all so there is no way to confirm this. The only mention of “Henricksen” is on Rose’s marriage certificate where it also notes “parents unknown.” The death certificate for Hannah that can be seen in the BDM might have more information. If the names of Rose’s parents were George HARRIS and Hannah SOLOMON, they had several other children, of which at least three were younger than Rose so it is unlikely they are the correct parents. It is not clear what happened to any of their other children.

The other story is that her family was attacked by the Maori and Rose was taken by them. She was later found wearing a Maori cloak and adopted by Peter and Victoria. I was given this story by someone else who is researching the family – a descendant of George Russell FELLOWS but she does not know where she heard these stories. I tried to confirm it with my Nana just before she died but her memory was not what it had been and she could not remember the story. There are no newspaper reports to confirm either story.

Another descendant of Rose recalls being told by Irene (Rose’s daughter) that Rose’s mother was Mary SHEARY/SHEERY/SHEEHY, was born in what is now Northern Ireland (and was Protestant), and married a Scottish man. So far, we have been unable to identify Rose’s parents based on this information – there are no birth records for a Rose in Dunedin with a mother of that name, and no marriage records in Ireland, Scotland, or New Zealand for Mary.

In the picture below of the family, the baby that is sitting on Rose’s knee to the left is little Eileen (the original picture that was taken shows Rose with Eileen and the boys, and also Tui and Irene beside them). Eileen was born in 1910 in Onehunga, Auckland, and died of influenza in December 1915 when she was just five years old. This was three years before the global influenza pandemic that started at the end of WWI.

Rose and Robert had seven children: Arthur Russell, Clement George, Tui Laurel Victoria, Irene Iris Graham, Eileen Lilac, Rose Rewa, and Robert Trevor (my grandfather). The boys were all given middle names from the family and the girls were all given first or middle names after flowers.

Children of Robert and Rose

Arthur Russell Fellowes

Clement “Clem” George Fellows

Tui Laurel Victoria Fellows

Irene Iris Graham Fellowes

Eileen Lilac Fellows

Rose Rewa Fellowes

Robert Trevor Fellowes

Irene Iris Graham Fellowes

Irene was born on October 9th, 1903. Irene was most likely born on Dog Island as her father was the assistant lighthouse keeper there until December 1903. Her death record from the indexes shows she was born in 1907 but her date of birth has been confirmed from her birth records. Note that the spelling of Irene’s surname is different from her older siblings – it seems that the family started using the new spelling from around 1903. There is a family story that one of Robert’s brothers was in trouble financially and Robert decided to change the spelling so he was not confused with his brother.

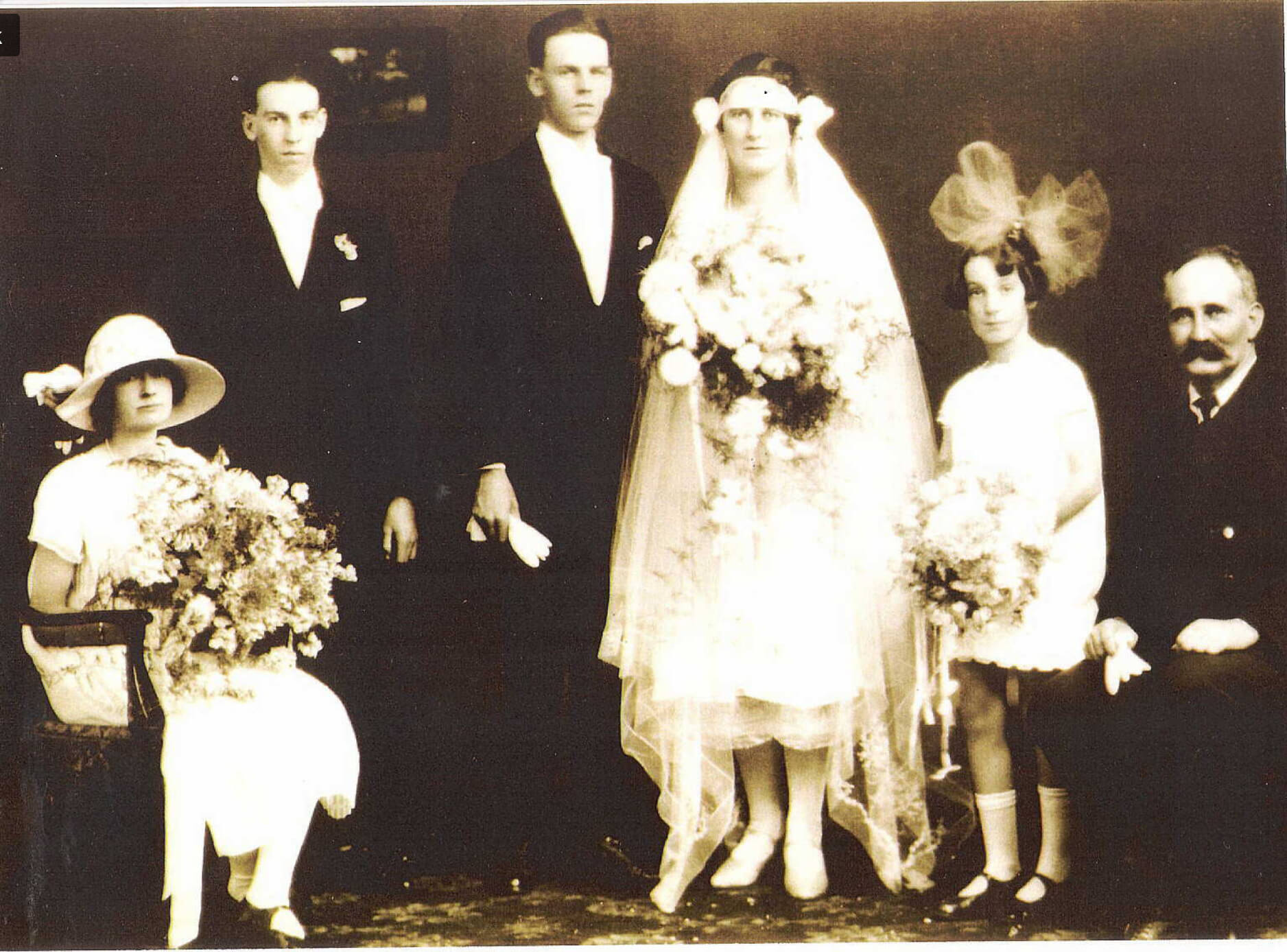

Irene married George Bruce BURDETT (1902-1977) on March 3rd, 1926. They had three daughters: Ann Margaret (1932-1990), Elizabeth Graham, and Frances Mary. Irene and George divorced in 1964. In 1946 and 1949, George is listed as a soldier on the electoral roll but there is no military record for him.

In Irene’s will, she appointed her daughter Ann Margaret ANDREWS as her trustee with her estate being shared between her three daughters.

In Irene and George’s wedding photo in the gallery below, the youngest sister Rose is the bridesmaid on the right with Irene’s father and possibly Irene’s bridesmaid on the left.

Rose Rewa “Bobbie” Fellowes

Bobbie was the second youngest child of Robert and Rose. She married Charles “Charlie” THACKWELL. They had four daughters. One of their daughters, Sharon, was my ballet teacher for several years when she lived next door to us. Sharon married Louis Statham and had two children who I babysat for when I was about 11-12 years old.

I remember visiting Bobbie and Charlie’s house often when I was a little girl. They lived in the city suburbs but had chickens and a large garden. For me, it seemed like a country paradise and I loved being given the job of collecting the eggs from the chicken coop whenever I would visit! They had a huge table in the kitchen that the whole family would gather around for meals and the conversation was always lively and fun. Charlie was a cobbler and had a little shed in the garden that he would mend shoes in. I loved visiting him while working on a pair of leather boots. He would lift me up onto his workbench and paint latex glue on my hand which I would peel off slowly once it set.

Sources

Angela Bain. Lighthouses of Foveaux Strait: A History. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.692.7349&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Robert Thomas FELLOWS

b. 2 Jun, 1873 in Darlington, Durham, England

d. 25 Feb, 1940 in Auckland, NZ

m. 22 Jun, 1943 in Auckland, NZ (Rose)

Mother: Elizabeth Graham

Father: George Russell Fellows

Siblings:

Frederick George Fellows

Arthur Russell Fellows

Rose Ann Adelaide HENRICKSEN

b. 9 Jun, 1876 in Dunedin, NZ

d. 11 Jun, 1938 in Auckland, NZ

Mother: Unknown

Father: Unknown

Children of Robert and Rose

Arthur Russell Fellowes (1894-1956)

Clement George Fellows (1897-1916)

Tui Laurel Victoria Fellows (1901-1968)

Irene Iris Graham Fellowes (1903-1978)

Eileen Lilac Fellows (1910-1915)

Rose Rewa Fellowes (1916-2000)

Robert Trevor “Fred” Fellowes (1918-1987)