My fifth great-grandparents on Dad’s side were Susannah BELL and David GREY. Susannah and David were married on November 24th, 1831 in St. Luke’s Church in Kent, England. They seemed to start their married life in financial difficulty. On December 24th, 1832, they were admitted to the Castle Street Workhouse, accompanied by their infant son, John David Grey, who was just five weeks old. They were discharged five days later.

Susannah again had to go to the workhouse for nine days in 1841, this time with all four of her children because David had absconded. At the time of discharge, Susannah was given a loan of $2 to buy a mangle. David turned up again in 1845, now married to Jane Gilbert with a daughter, Frances.

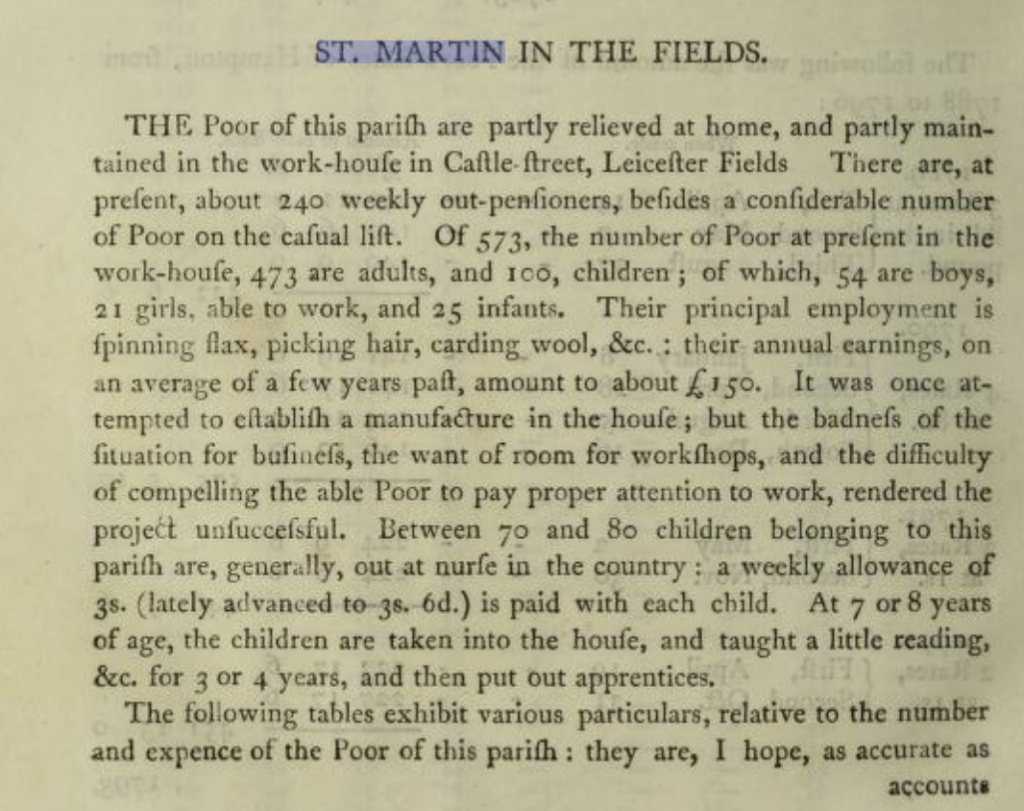

The Castle Street workhouse was located in St-Martin-in-the-Fields in London. Originally built in 1665 in the churchyard of St Martin Church, the workhouse was one of the largest in the country capable of housing up to 700 people. A 1797 survey (Eden, 1797) on the workhouse reads (note that the letter “s” at this time was written as “f”):

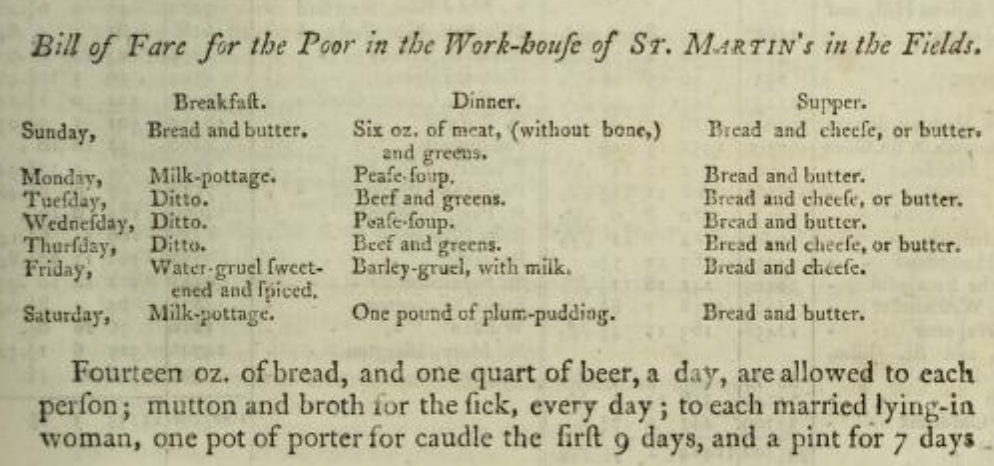

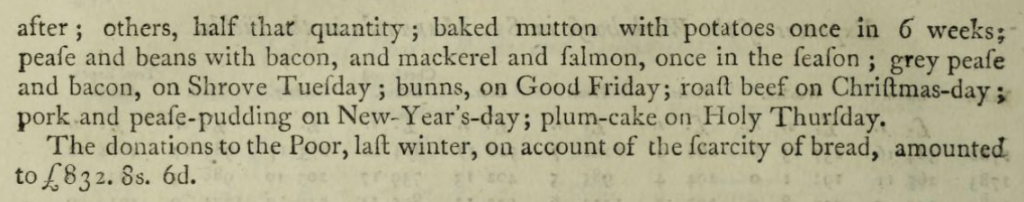

Eden also outlines the food that is provided for the “inmates.”

By 1865, the conditions of St Martin were appalling, as outlined by the Lancet Sanitary Commission:

The male tramp ward, in particular, struck us with horrified disgust. We scarcely had a fair glance at it on the occasion of our first visit, being accompanied by the visiting committee; (for whose edification, by the way, we strongly suspect it had been furbished up in an unusual manner); but a few days since we revisited it, and the impression produced on our minds is that we have seldom seen such a villanous hole. It is situated completely underground, and is approached by an almost perpendicular flight of stone steps, leading to a grated iron door, through which one passes into an ill-smelling water closet, which forms the antechamber of messieurs the tramps.

The apartment at the moment of our entrance (about midday) was being ventilated and cleaned by a very nasty-looking warder. The ventilation business seemed difficult, for there, is but one window, closely grated, to this apartment, in with some sixteen or twenty people sleep, and that is quite close up to the watercloset end. From the other part of the room, in which the beds (or shelves) for the tramps are situated, and in which the nasty-looking man was making feeble movements with a brush, there arose a concentrated vagrant-stink which

fairly drove us out, not without threatenings of sickness. The bathroom, in which the ” casuals” are facetiously supposed to wash before retiring to rest, is a still more dungeon like place; or rather (to use a less dignified and more appropriate phrase) it is like a very bad beer-cellar, through the obscurity of which one may dimly perceive a tin bath, while one’s nose is assaulted by a new and more dreadful stench.

Both bath-room and sleeping-room were extremely dirty; and considering that the allowance of cubic space for each sleeper is but 294 feet under the most favourable circumstances, it is really a marvel that typhus does not spontaneously arise among the temporary inhabitants of this disreputable ward. If any of the tramps fall sick, they are taken up into a miserable ward in a one-storied building at the east end of the premises, and closely adjoining the dead-house, in which they are greatly overcrowded when the place happens to be full and the bed-furniture of which is squalid and mean.

The full report makes depressing, while fascinating, reading.

In 1854, a medical report outlines the treatment that was used to manage diarrhoea by the medical officer:

IN a communication received from Dr. Bainbridge, medical officer of St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields, he says:-

“I have to state, that up to the present time we have not had more than the usual amount of diarrhoea at this season of the year, and not, as yet, one case of Asiatic cholera.

“My usual treatment in these cases of diarrhoea, where there have been frequent dejections, with violent griping pains and sometimes sickness, has been to administer one or two grains of solid opium, followed up by chalk mixture, five ounces and a half; tincture of opium, a drachm; tincture of

catechu, half an ounce; aromatic confection, a drachm and a half. Two tablespoonfuls to be taken every hour. This has generally acted like a charm. In this stage the disease is completely under control.

“In 1849, I had a district of the parish assigned to me as well as the workhouse, and, from March to October, I attended 1669 cases, the principal part being in August, September, and October; out of these I had twenty-seven deaths.

“Where the deaths occurred, with one exception, the patients, when I first saw them, were labouring under vomiting, rice-water purging, the peculiar sepulchral hoarseness, suppression of urine, cold tongue, breath and surface,

cramps, blue skin, and were sometimes nearly pulseless, indeed, in complete collapse.

“To several of these I gave large quantities of ammonia and brandy. In some I tried dilute sulphuric acid; in others, Dr. Ayre’s plan of scruple doses of calomel every ten minutes, mustard poultices, frictions, &c., but no remedies appeared to have the slightest effect, as there was no absorption.

“The conclusion to which I have come from actual observation of this disease is, that the remedies I have mentioned are almost specific in ninety-nine cases out of one hundred, if given sufficiently early. Where the patients are nearly pulseless, with rice-water motions and general collapse, I believe all remedies are unavailing.”

It is hard to imagine how mercury chloride, ammonium, sulphuric acid and opium were ever believed to have helped these poor souls!

Glossary

Cachectic diseases of infancy: a wasting disease seen in infants, probably due to malnutrition

Catechu: an extract from the acacia tree

Calomel: mercury chloride used as a fungicide and pergorative (to cause vomiting)

Drachm: one eight of an ounce

Phthisis: Pulmonary tuberculosis

Sources

Eden, F. M. (1797). The state of the poor; or, an history of the labouring classes in England, from the conquests to the present period. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/b28773135_0002